The terrible crime at Richmond at last,

On Catherine Webster now has been cast,

Tried and found guilty she is sentenced to die.

From the strong hand of justice she cannot fly.

She has tried all excuses but of no avail,

About this and murder she’s told many tales,

She has tried to throw blame on others as well,

But with all her cunning at last she has fell.

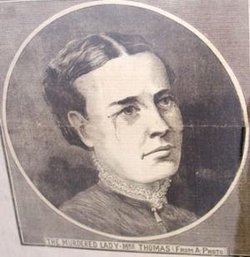

One of the most notorious crimes of the late Victorian era in Britain was the murder of Julia Martha Thomas by her Irish maid, Kate Webster in March 1879. A widow, Julia Thomas lived at 2 Mayfield Cottages on Park Road in Richmond. It was a quiet and respectable area. A small, well-dressed lady of about fifty, Julia was said to  have had an excitable temperament and was regarded by many as eccentric. She was not particularly wealthy, but she always dressed up and wore jewellery to give the impression of prosperity. Her employment of a live-in maid was more to do with status than practicality. However, she had a reputation for being a harsh employer and she had difficulty finding and retaining servants.

have had an excitable temperament and was regarded by many as eccentric. She was not particularly wealthy, but she always dressed up and wore jewellery to give the impression of prosperity. Her employment of a live-in maid was more to do with status than practicality. However, she had a reputation for being a harsh employer and she had difficulty finding and retaining servants.

Kate Webster was born as Kate Lawler in County Wexford, Ireland, around 1849. She was said to be “a tall, strongly-made woman of about 5 feet 5 inches in height with sallow and much freckled complexion and large and prominent teeth.” Much of her early life is unclear but she claimed to have been married to a sea captain called Webster by whom she had four children, all of whom died, as did her husband, within a short time of each other. She was imprisoned for theft in Wexford in December 1864, when she was only about 15 years old. She moved to England in 1867 and fell into a life of crime, being frequently imprisoned for robbery. However, she was recommended as a maid to Julia Thomas by someone who had employed her temporarily. Julia engaged her immediately without checking out her character or past.

Their relationship rapidly deteriorated with Julia disliking the quality of Kate Webster’s work. Kate said of Julia Thomas: “At first I thought her a nice old lady … but I found her very trying, and she used to do many things to annoy me during my work. When I had finished my work in my rooms, she used to go over it again after me, and point out places where she said I did not clean, showing evidence of a nasty spirit towards me.” The situation reached a crisis point and it was arranged that Kate Webster would leave Julia’s service on 28th February. Julia recorded her decision in what was to be her last diary entry: “Gave Katherine warning to leave.”

But Kate persuaded her employer to give her a few days grace until Sunday 2nd March. She had Sunday afternoons off as a half-day and was expected to return in time to help Julia prepare for evening service. But Webster returned late, delaying Julia’s departure. The two women argued and several members of the congregation later reported that Julia had appeared “very agitated” on arriving at the church. Julia returned home and confronted Webster. According to Webster’s eventual confession:

“Mrs. Thomas came in and went upstairs. I went up after her, and we had an argument, which ripened into a quarrel, and in the height of my anger and rage I threw her from the top of the stairs to the ground floor. She had a heavy fall, and I became agitated at what had occurred, lost all control of myself, and, to prevent her screaming and getting me into trouble, I caught her by the throat, and in the struggle she was choked, and I threw her on the floor.”

The neighbours heard a single thump like that of a chair falling over but paid no heed to it at t he time. Next door, Webster began disposing of the body by dismembering it and boiling it in the laundry copper and burning the bones in the hearth. The neighbours later said that they had noticed an unusual and unpleasant smell. However, the activity at 2 Mayfield Cottages did not seem to be out of the ordinary, as Monday was traditionally wash day. Over the next couple of days Webster continued to clean the house and Thomas’ clothes and put on a show of normality for people who called. Behind the scenes she was putting Thomas’ dismembered remains into a black Gladstone bag and a wooden bonnet-box. These were disposed of in the Thames. She was unable to fit the murdered woman’s head and one of the feet into the containers and disposed of them separately, throwing the foot onto a rubbish heap in Twickenham. The head was buried under the Hole in the Wall pub’s stables a short distance from Julia’s’ house, where it was found 131 years later.

he time. Next door, Webster began disposing of the body by dismembering it and boiling it in the laundry copper and burning the bones in the hearth. The neighbours later said that they had noticed an unusual and unpleasant smell. However, the activity at 2 Mayfield Cottages did not seem to be out of the ordinary, as Monday was traditionally wash day. Over the next couple of days Webster continued to clean the house and Thomas’ clothes and put on a show of normality for people who called. Behind the scenes she was putting Thomas’ dismembered remains into a black Gladstone bag and a wooden bonnet-box. These were disposed of in the Thames. She was unable to fit the murdered woman’s head and one of the feet into the containers and disposed of them separately, throwing the foot onto a rubbish heap in Twickenham. The head was buried under the Hole in the Wall pub’s stables a short distance from Julia’s’ house, where it was found 131 years later.

However, the next day, the box was found washed up in shallow water next to the river bank about a mile downstream. The discovery was immediately reported to the police. Around the same time, the foot and ankle were also found. Although it was clear that all of the remains belonged to the same corpse, there was nothing to connect them and no means to identify the remains. The doctor who examined the body parts erroneously attributed them to “a young person with very dark hair”. An inquest returned an open verdict and the unidentified remains were laid to rest in Barnes Cemetery on 19 March. The newspapers dubbed the unexplained murder the “Barnes Mystery”, amid speculation that the body had been used for dissection and anatomical study.

Webster continued to live at 2 Mayfield Cottages while posing as Julia Thomas, wearing her late employer’s clothes and dealing with tradesmen under her newly assumed identity. On 9 March she reached an agreement with John Church, a local publican, to sell Thomas’ furniture and other goods. By the time the removal vans arrived on 18 March, the neighbours were becoming increasingly suspicious as they had not seen Julia for nearly two weeks. Her next-door neighbour, Miss Ives, asked the deliverymen who had ordered the goods removed. They replied “Mrs. Thomas” and indicated Webster. Realising that she had been exposed, Webster fled. The police were called in and searched 2 Mayfield Cottages. There they discovered blood stains, burned finger-bones in the hearth and fatty deposits behind the copper, as well as a letter left by Webster giving her home address in Ireland. They immediately put out a “wanted” notice giving a description of Webster.

Scotland Yard detectives soon discovered that Webster had fled back to Ireland. The head constable of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in Wexford realised that the woman being sought by Scotland Yard was the same person whom his force had arrested 14 years previously for larceny. The RIC were able to trace her to her uncle’s farm near Enniscorthy and arrested her there on 29 March. She was escorted back to England to stand trial.

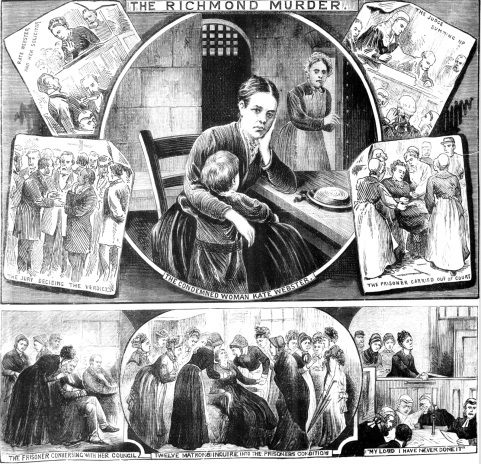

The murder caused a sensation on both sides of the Irish Sea. When the news broke, many people travelled to Richmond to look at Mayfield Cottages. The crime was just as notorious in Ireland; as Webster travelled under arrest from Enniscorthy to Dublin, crowds gathered to gawk and jeer at her at nearly every station between the two locations. The pre-trial magistrates’ hearings were attended by many. Webster went on trial at the Old Bailey on 2 July 1879. The prosecution was led by the Solicitor General, Sir Hardinge Giffard. Webster was defended by a prominent London barrister, Warner Sleigh, and the case was presided over by Mr. Justice Denman. The trial drew intense interest from all levels of society; on the fourth day, the Crown Prince of Sweden – the future King Gustaf V – turned up to watch the proceedings.

Over the course of six days, the court heard a succession of witnesses piecing together the complicated story of how Thomas had met her death. Webster had attempted before the t rial to implicate the publican John Church and her former neighbour Porter, but both men had solid alibis and were cleared of any involvement in the murder. She pleaded not guilty and her defence sought to emphasise the circumstantial nature of the evidence and highlighted her devotion to her son as a reason why she could not have been capable of the murder. However, Webster’s public unpopularity, impassive demeanour and scanty defence counted strongly against her. A particularly damning piece of evidence came from a bonnetmaker named Maria Durden who told the court that Webster had visited her a week before the murder and had said that she was going to Birmingham to sell some property, jewellery and a house that her aunt had left her. The jury interpreted this as a sign that Webster had premeditated the murder and convicted her after deliberating for about an hour and a quarter.

rial to implicate the publican John Church and her former neighbour Porter, but both men had solid alibis and were cleared of any involvement in the murder. She pleaded not guilty and her defence sought to emphasise the circumstantial nature of the evidence and highlighted her devotion to her son as a reason why she could not have been capable of the murder. However, Webster’s public unpopularity, impassive demeanour and scanty defence counted strongly against her. A particularly damning piece of evidence came from a bonnetmaker named Maria Durden who told the court that Webster had visited her a week before the murder and had said that she was going to Birmingham to sell some property, jewellery and a house that her aunt had left her. The jury interpreted this as a sign that Webster had premeditated the murder and convicted her after deliberating for about an hour and a quarter.

Shortly after the jury returned its verdict and just before the judge was about to pass sentence, Webster was asked if there was any reason why sentence of death should not be passed upon her. She pleaded that she was pregnant in an apparent bid to avoid the death penalty. The Law Times reported that “upon this a scene of uncertainty, if not of confusion, ensued, certainly not altogether in harmony with the solemnity of the occasion.” The judge commented that “after thirty-two years in the profession, he was never at an inquiry of this sort.” Eventually the Clerk of Assizes suggested using the archaic mechanism of a jury of matrons, constituted from a selection of the women attending the court, to rule upon the question of whether Webster was “with quick child”. Twelve women were sworn in along with a surgeon named Bond, and they accompanied Webster to a private room for an examination that only took a couple of minutes. They returned a verdict that Webster was not “quick with child.”

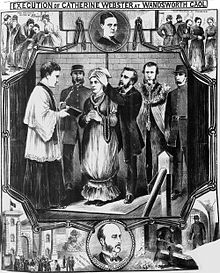

Before she was executed, Webster made two statements. The first was false in which she tried to implicate two others; the second in which she took full responsibility. She was hanged the following day at Wandsworth Prison at 9 am, where the hangman, William Marwood, used his newly developed “long drop” technique to cause instantaneous death. She was buried in an unmarked grave in one of the prison’s exercise yards. The crowd waiting outside cheered as a black flag was raised over the prison walls, signifying that the death sentence had been carried out.

The trial was a sensation and was widely reported in the press, both in Ireland and Britain. Within weeks of her arrest, and well before she had gone to trial, Madame Tussaud’s created a wax effigy of her and put it on display for those who wished to see the “Richmond Murderess”.  It remained on display well into the twentieth century. Within days of her execution an enterprising publisher rushed into print a souvenir booklet for the price of a penny, “The Life, Trial and Execution of Kate Webster. The Illustrated Police News published a souvenir cover depicting an artist’s impression of the day of the execution. The case was also commemorated, while it was still ongoing, by street ballads—musical narratives set to the tune of popular songs.

It remained on display well into the twentieth century. Within days of her execution an enterprising publisher rushed into print a souvenir booklet for the price of a penny, “The Life, Trial and Execution of Kate Webster. The Illustrated Police News published a souvenir cover depicting an artist’s impression of the day of the execution. The case was also commemorated, while it was still ongoing, by street ballads—musical narratives set to the tune of popular songs.

Webster herself was characterised as malicious, reckless and wilfully evil. Servants were expected to be deferential; her act of extreme violence towards her employer was deeply disquieting. At the time, about 40% of the female labour force was employed as domestic servants for a very wide range of society. Servants and employers lived and worked in close proximity, and the honesty and orderliness of servants was a constant cause of concern.

Another cause of revulsion against Webster was her attempt to impersonate her dead employer for two weeks, implying that middle-class identity amounted to little more than cultivating the right demeanour and having the appropriate clothes and possessions, whether or not they had been earned.

Perhaps most disturbingly for many Victorians, Webster was seen as having violated the expected norms of femininity. Victorian women were supposed to be moral, passive and physically weak. Webster was seen as quite the opposite and her appearance and behaviour were seen as key signs of her inherently criminal nature. Her behaviour in court and her sexual history also counted against her. Being Irish was a significant factor in the widespread revulsion felt towards Webster in Great Britain. The depiction of Webster as “hardly human” was of a piece with the public and judicial perceptions of the Irish as innately criminal.

In 1952, the naturalist David Attenborough and his wife Jane bought a house situated between the former Mayfield Cottages (which still stand today) and the Hole in the Wall pub. The pub closed in 2007 and fell into dereliction but was bought by Attenborough in 2009 to be redeveloped. On 22 October 2010, workmen carrying out excavation work at the rear of the old pub uncovered what turned out to be a woman’s skull. It was immediately speculated that  the skull was the missing head of Julia Martha Thomas, and the coroner asked Richmond police to carry out an investigation into the identity and circumstances of death of the skull’s owner. Carbon dating found that it was dated between 1650 and 1880, but it had been deposited on top of a layer of Victorian tiles. The skull had fracture marks consistent with Webster’s account of throwing Thomas down the stairs, and it was found to have low collagen levels, consistent with it being boiled. In July 2011, the coroner concluded that the skull was indeed that of Thomas. DNA testing was not possible as she had died childless and no relatives could be traced; in addition, there was no record of where the rest of her body had been buried.

the skull was the missing head of Julia Martha Thomas, and the coroner asked Richmond police to carry out an investigation into the identity and circumstances of death of the skull’s owner. Carbon dating found that it was dated between 1650 and 1880, but it had been deposited on top of a layer of Victorian tiles. The skull had fracture marks consistent with Webster’s account of throwing Thomas down the stairs, and it was found to have low collagen levels, consistent with it being boiled. In July 2011, the coroner concluded that the skull was indeed that of Thomas. DNA testing was not possible as she had died childless and no relatives could be traced; in addition, there was no record of where the rest of her body had been buried.

The coroner recorded a verdict of unlawful killing, superseding the open verdict recorded in 1879. The cause of Thomas’s death was given as asphyxiation and a head injury. The police called the outcome, “a good example of how good old-fashioned detective work, historical records and technological advances came together to solve the Barnes Mystery.”

Interesting article! I can not wrap my head around how someone can kill someone and then cut them up and boil them. I have a strong constitution but ewwwww…lol

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes it was pretty nasty and I suppose that was why people were so shocked and fascinated by the case. She had an illegitimate son and I’d love to know what happened to him. Her family send him to the workhouse in Wexford because of what she did.

LikeLike

Fascinating story, Pam…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is absolutely mind blowing. Historically, women have rarely committed murders, until recent times. Great–although grueling–story, Pam.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I don’t think Kate Webster was a particularly nice person and your worst nightmare for a servant!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for a good read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with Deb – mind-blowing. Excellent article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I commented on First Night History, this is ripe for a film or TV adaptation. I have already mentally ‘cast’ Vicky McClure as Kate Webster, and I fancy Sue Johnston as Mrs Thomas! Thanks for following my blog, and I look forward to seeing this on the BBC!

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are a few books out there but haven’t heard of a tv/film adaptation. Agree – would be very interesting. Webster must have been some cookie – I can understanding killing someone in a rage but cutting them up and boiling them – so cold-blooded!

LikeLike

Nothing changes, was watching a programme last night about Dennis Neilsson who killed at least 15 young men and boiled them after cutting them up. So very sad. This is fascinating. Thanks.

LikeLike